By Jonathan Brockopp

Over the years, I have noticed that shopkeepers in North Africa and the Middle East seem to value the relationship as much as they do the sale; the same truth holds for working with manuscripts, which is never simply a transactional affair. I have benefited enormously from the generosity, training, and long experience of my North African colleagues, such as Dr. Hamid Lahmer, Professor of Islamic Law at the University of Fez.

After our initial meeting, in the Moroccan tradition of hospitality, Dr. Lahmer invited me to dinner at his home, drove me out to the family farm in the countryside, and arranged for me to lecture to his students at the University. He also gave me the introductions I needed to work with the manuscripts of the Qarawiyyīn collection in Fez.

The Qarawiyyīn collection is now housed in a large, modern building, with excellent facilities and staff. As usual, I was primarily interested in their oldest Mālikī texts dating to the fourth hijrī century, many of which Joseph Schacht had written about in his research trips in the 1960s.[1] Most of these, such as the important copies of Ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥakam's al-Mukhtaṣar al-Kabīr, are written on parchment and still in fairly good shape, but a few are on paper.

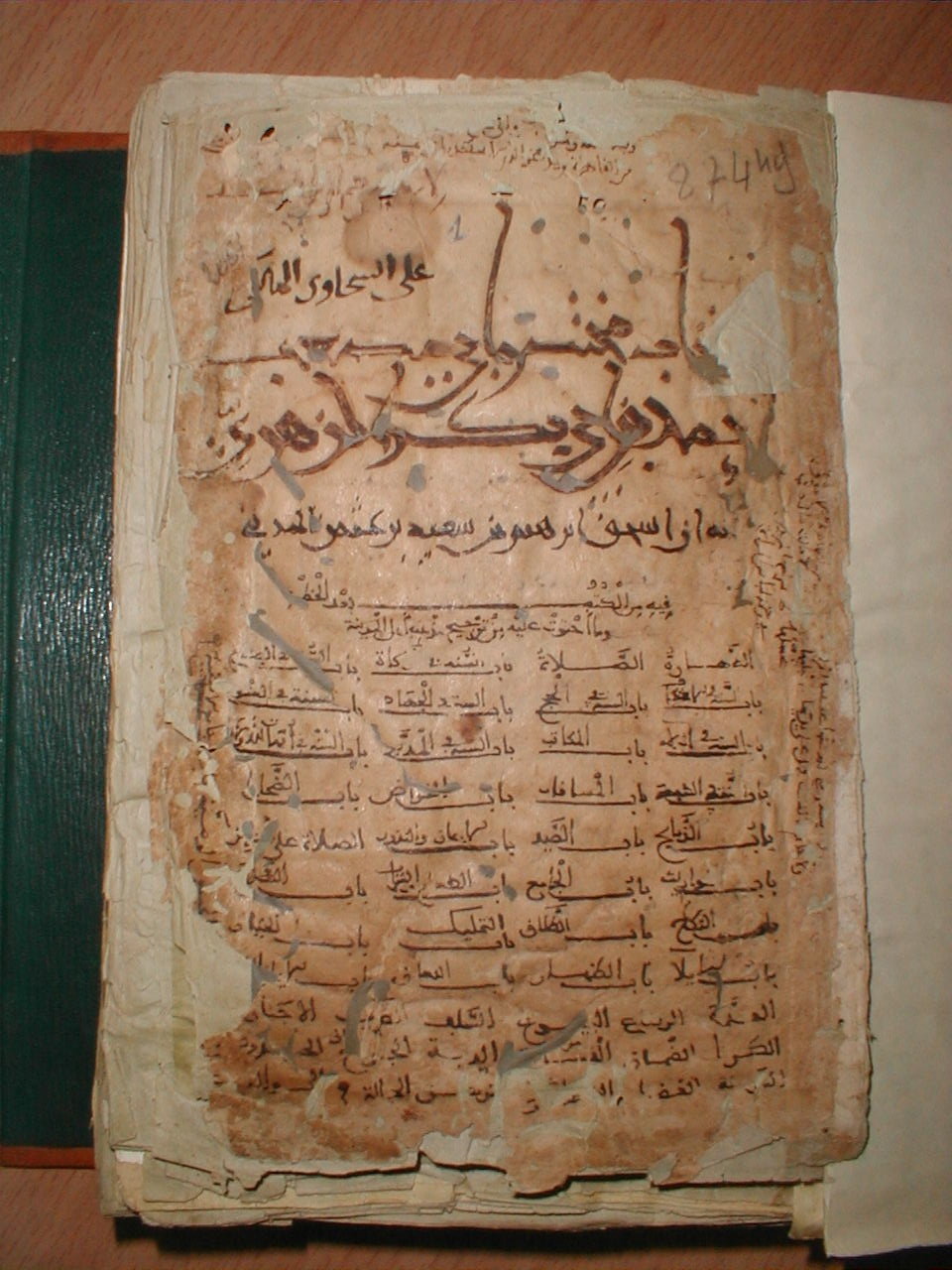

One of the oldest-dated paper manuscripts in that collection is Number 874, the Mukhtaṣar by Abū Musʿab Aḥmad b. Abī Bakr al-Qāsim al-Zuhrī (d. 242/856).[2] Abū Musʿab lived and worked in Medina, and if his birth date of 150/767 is correct, he would have been twenty-nine years old when Mālik b. Anas died (179/795).[3]

In this early period, a mukhtaṣar should be understood as a compendium of law, not as a summary or reduction of another, larger work as was common in later periods. I have written quite a bit on early mukhtaṣars and their meaning for the development of Islamic law,[4] but it is the material qualities of this particular manuscript that I want to focus on here.

As Schacht had noted, the manuscript was heavily damaged, but I was impressed with the high quality of the paper, especially since the manuscript was clearly dated to 359/ 969–70 on the colophon.[5] In my previous essay, I pointed out that Azhar Manuscript 1655, which may be from AH 405/1015, was already one of the oldest-dated literary manuscripts on paper, and in my next essay, I'll focus on two paper manuscripts in the Kairouan collection that appear to date from the third century AH. What I have since come to understand is that the history of early Islamic paper is still being written.

Scholars concur that paper was first produced in China and then only slowly moved West.[6] What remains unclear is the precise chronology of that transmission. As recently as 2017, Jonathan Bloom placed the arrival of paper in North Africa in the eleventh century CE, [7] apparently unaware of this manuscript that Schacht had described fifty years earlier, in 1965. It is true, however, that colophons can be copied, and manuscripts can move; therefore, it is not immediately obvious that this manuscript should be taken as evidence of paper manufacture in the West in the tenth century.

Bloom relies on the nineteenth-century work of Josef von Karabacek, who analyzed hundreds of paper documents found in the collection of the Archduke Rainer, now in the Austrian National Library.[8] Von Karabacek demonstrated convincingly that the tenth century was the key moment when papyrus finally fell out of fashion, with the oldest-dated paper from the year 300/912–13.[9] If paper came from China, and if the earliest paper in Egypt is from AH 300, then allowing another century for westward diffusion might seem to make sense, especially since von Karabacek held that most of this paper was actually produced in Iraq and transported to Egypt.

However, more evidence has come to light since 1886, including six early Arabic paper documents that Nabia Abbott dated to between 254/868 and 297/909; she also described a fragment from the Thousand Nights on paper with scribal doodling repeatedly writing the year AH 266.[10] We also now have evidence that paper was used much earlier, during the Umayyad period, based on discoveries in Tajikistan in 2008.[11]

While this local usage of materials does not provide evidence of either local manufacture or dissemination farther west, it is an important data point that should help reset our thinking about when and how paper was used. New techniques of materials analysis might also help us determine where these examples of early paper were produced. Finally, paper fragments from the fourth/tenth century and earlier have been preserved in the Cairo Geniza, so much so that Marina Rustow avers: "The number of early paper texts in Arabic is doubtless greater than we know."[12]

In addition to underestimating the widespread use of paper in the fourth/tenth century, it is my judgement that many scholars still underestimate the sophistication of the far west of the Islamic world.[13] There is, frankly, no reason to think that innovations such as paper manufacture took anywhere near a century to move west. In fact, we have rich manuscript evidence that scholars in Spain and North Africa were very much keeping up with trends in the East and even setting their own trends. Menahem Ben Sasson has demonstrated this very dynamic for the Jewish community of Kairouan, and the Cairo Geniza also presents ample evidence of a robust and effective trade network.[14]

So, it is not only possible that the courts of Fez and Cordoba had paper manufacturers in the fourth/tenth century, it is likely. After all, our earliest treatise on papermaking in the Islamic world comes not from Iraq but from the Amazigh Amīr of Ifrīqiya, al-Muʿizz b. Bādīs,[15] who died in 454/1062.

Returning to Qarawiyyīn 874, Schacht noted the clear Andalusian script;[16] together with its current location in Fez, this suggests either that the manuscript was copied by an Andalusian scholar on his rihlat ṭalab al-ʿilm in the East and brought home as a souvenir, or it was copied out in the West. In either case, it is evidence of Andalusian scholars' strong interest in the latest legal developments in the East, as well as in the latest techniques of book manufacture.

Notes:

[1] Joseph Schacht, "Sur quelques manuscrits de la bibliothèque de la mosquée d'al-Qarawiyyīn à Fès. Études d'orientalisme (Adrien Maisonneuve, 1962), 1: 271–84.

[2] Fihris Makhṭūṭāt Khizānat al-Qarawīyīn, ed. Muḥammad al-ʻĀbid Fāsī (Dār al-Kitāb, 1979–89). For Abū Musʿab, see Shams al-Dīn al-Dhahabī, Taʾrīkh al-Islãm, ed. ʿUmar 'Abd al-Salām Tadmurī (Dār al-Kitāb al-ʿArabī, 1991), 18:153–55; Fuat Sezgin, Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums (Brill, 1967) 1:471–72; Schacht, "Sur quelques manuscrits," 1:271–84.

[3]Joseph Schacht, "On Abū Musʿab and his `Mujtasar'," al-Andalus 30, no. 1 (1965), 1–14. Schacht's article is of great importance in providing a brief biography of Abū Musʿab, and in analyzing this manuscript and recognizing several of its key features.

[4] See Jonathan Brockopp, "Early Islamic Jurisprudence in Egypt: Two scholars and their Mukhtasars," International Journal of Middle East Studies 30 (1998): 167-82; and "The Minor Compendium of Ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥakam (d. 214/829) and its reception in the early Mālikī school," Islamic Law and Society 12, no. 2 (2005): 149–81.

[5] Schacht, "On Abū Musʿab," plate IV.

[6] Jonathan M. Bloom, "Papermaking: The Historical Diffusion of an Ancient Technique," in Mobilities of Knowledge, ed. Heike Jöns, Peter Meusburger and Michael Heffernan (Berlin: Springer, 2017), 51–66.

[7] Bloom, "Papermaking," 54; See also map, p. 55.

[8] Josef Ritter von Karabacek, Mitteilungen aus der Sammlung Papyrus Erzherzog Rainer (K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, 1886), 96–97. Only a small portion of the estimated 40,000 pieces of paper in this collection has been analyzed.

[9] von Karabacek, Mitteilungen, 97. A search of the Austrian National Library's online catalog did not reveal any of these earliest paper examples, but did include examples from the tenth century. See, for example, Schreibübungen und Entwürfe eines Steuerbeamten. Inventarnummer: A. Ch. 10442 Pap, dated ca. 307/919.

[10] Nabia Abbott, "A Ninth-Century Fragment of the 'Thousand Nights' New Light on the Early History of the Arabian Nights," Journal of Near Eastern Studies 8, no. 3 (1949): 129–64.

[11] Ofir Haim, Michael Shenkar and Sharof Kurbanov, "The Earliest Arabic Documents Written on Paper: Three Letters from Sanjar-Shah (Tajikistan)," Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 43 (2016): 141–90.

[12] Marina Rustow, The Lost Archive: Traces of a Caliphate in a Cairo Synagogue (Princeton University Press, 2020), 474, n. 42 (referencing p. 124).

[13] Schacht, "On Abū Musʿab," 13–14.

[14] Menahem Ben-Sasson, Tsemihat ha-kehilah ha-Yehudit be-artsot ha-Islam: Kairavan, 800–1057 (The emergence of the local Jewish community in the Muslim world: Qayrawān 800–1057) (Hotsaʼat sefarim ʻa. sh. Y.L. Magnes, 1996); S.D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society (University of California Press, 1969–1987).

[15] Al-Muʿizz b. Bādīs, "Mediaeval Arabic Bookmaking and its Relation to Early Chemistry and Pharmacology" [translation of ʿUmdat al-kuttāb wa-ʿuddat dhawī l-albāb] by Martin Levey, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia, 1962), 1–79.

[16] Schacht, "On Abū Musʿab," 13.

Suggested Bluebook citation: Jonathan Brockopp, Four manuscripts from the Mālikī tradition: Qarawiyyīn, 874, Islamic Law Blog (Nov. 13, 2025), https://islamiclaw.blog/2025/11/13/four-manuscripts-from-the-maliki-tradition-qarawiyyin-874/.

Suggested Chicago citation: Jonathan Brockopp, "Four manuscripts from the Mālikī tradition: Qarawiyyīn, 874," Islamic Law Blog, November 13, 2025, https://islamiclaw.blog/2025/11/13/four-manuscripts-from-the-maliki-tradition-qarawiyyin-874/.

No comments:

Post a Comment